Basic of Lattice-based Cryptography

The cryptography that secures the Internet is evolving, and it’s time to catch up especially when we know that in the future, quantum computers will break both ECC and RSA. In this post, I will give a brief introduction to lattice-based cryptography, one of the new post-quantum cryptographic schemes.

Vector Spaces

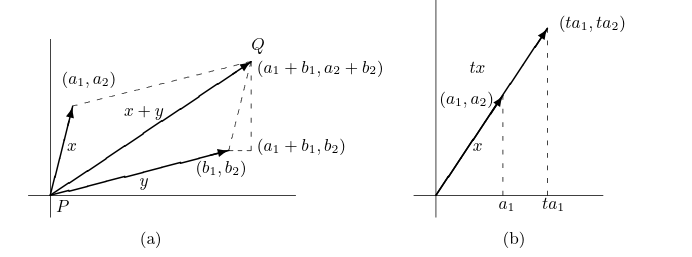

Recall a vector space $V$ over a field $K$ (said $\mathbb{R}$ or $\mathbb{C}$) is a set of “vectors”, with the addition of vectors and multiplication of a vector by a scalar, satisfying certain properties:

- For all vectors $x$ and $y$, $x+y = y+x$

- For all vectors $x,y$ and $z$, $(x+y)+z = x+(y+z)$

- There exists a vector denoted $0$ such that $x+0 = x$ for each vector $x$.

- For each vector $x$, there is a vector $y$ such that $x+y = 0$.

- For each vector $x$ and an element $1 \in K$, we have $1x =x$. We call $1$ the multiplicative identity in $K$.

- For each pair of elements $a,b \in K$ and $v \in V$ we have $a(bv) = (ab)v$

- For each element $a\in K$ and each pair of vector $x,y$, we have $a(x+y)=ax+ay$

- For each pair of elements $a,b \in K$ and each vector $x$, we have $(a+b)x = ax+bx$

Since we know in linear algebra that every $n$-dimensional vector space over $\mathbb{R}$ is isomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^n$, let focus on the case of $\mathbb{R}^n$, which can be realized as a $n$-tuple of real number $(x_1,x_2,…,x_n)$, where each $x_i \in \mathbb{R}$.

Two $n$-tuples $(a_1,a_2,…,a_n)$ and $(b_1,b_2,…,b_n)$ are called equal if and only if $a_i = b_i$ for all $i = 1,2,…,n$.

For $n=2$, we have our familiar 2D plane, where each vector can be represented as an arrow from the origin $(0,0)$ to the point $(x_1,x_2)$. This helps us imagine what lattice looks like in a moment.

For example, the set $\lbrace (0,1),(1,0) \rbrace$ can generate every vector $(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2$ by the linear combination $x(1,0) + y(0,1) = (x,y)$, where $x,y \in \mathbb{R}$.

We can generalize this idea to $n$-dimension vector space $\mathbb{R}^n$ by taking the linear combination of the standard basis vectors $\lbrace (1,0,0,…,0),(0,1,0,…,0),…,(0,0,0,…,1) \rbrace$.

Next, we need to understand what is a subspace of a vector space.

Basically, they are the subset of a vector space that is also a vector space and possess the same structure as the set under consideration.

Definition: A subset $W$ of a vector space $V$ over a field $K$ is called a subspace of $V$ if $W$ is a vector space over $K$ with the operations of addition and scalar multiplication defined on $V$.

For a vector $v$ in $V$, if there exist a finite number of vectors $w_1,w_2,…,w_k$ in $W$ and scalars $a_1,a_2,…,a_k$ in $K$ such that $v = a_1w_1 + a_2w_2 + … + a_kw_k$, then we say that $v$ is a linear combination of the vectors $w_1,w_2,…,w_k$.

The set consisting of all linear combinations of the vectors in $W$ is called the span of $W$ and is denoted by $span(W)$.

By default, we have $span(\emptyset) = \lbrace 0 \rbrace$.

The span of any subset $W$ of a vector space $V$ is a subspace of $V$. Moreover, any subspace of $V$ that contains $W$ must also contain $span(W)$.

Definition: A subset $W$ of a vector space $V$ generates $V$ if $span(W)=V$.

For example, the vectors $(1,1,0),(1,0,1),(0,1,1)$ generate $\mathbb{R}^3$ since any vector $(x,y,z) \in \mathbb{R}^3$ can be written as a linear combination of these vectors:

We have known that there are some vectors that can be written as a linear combination of other vectors in the same set. This lead us to two important definitions: linear independence and basis.

Definition: A subset $W$ of a vector space $V$ is called linearly dependent if there exist a finite number of distinct vectors $w_1,…,w_k$ in $W$ and scalars $a_1,a_2,…,a_k$, not all zero, such that $a_1w_1 + a_2w_2 + … + a_kw_k = 0$. If no such scalars exist, then $W$ is called linearly independent.

Thus, a set of vectors is linearly independent if no vector in the set can be expressed as a linear combination of the other vectors in the set.

We can observe that, if $W$ generates $V$ and is linearly independent, then every vector in $V$ can be uniquely expressed as a linear combination of the vectors in $W$. $W$ is then called a basis of $V$.

Definition: A basis $\beta$ for a vector space $V$ is a linearly independent subset of $V$ that generates $V$.

If $V$ has a finite basis, then every basis of $V$ has the same number of elements. This number is called the dimension of $V$ and is denoted by $dim(V)$.

Lattices

Books and resources

- https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/032.pdf